The copyright industry is not going quietly. The legitimacy of its monopolist and consumerist practices are still upheld by policymakers and panicking creators who haven’t seen any real alternative in action. I humbly submit my silly cartoon about people with inanimate objects for heads as a first step in that direction.

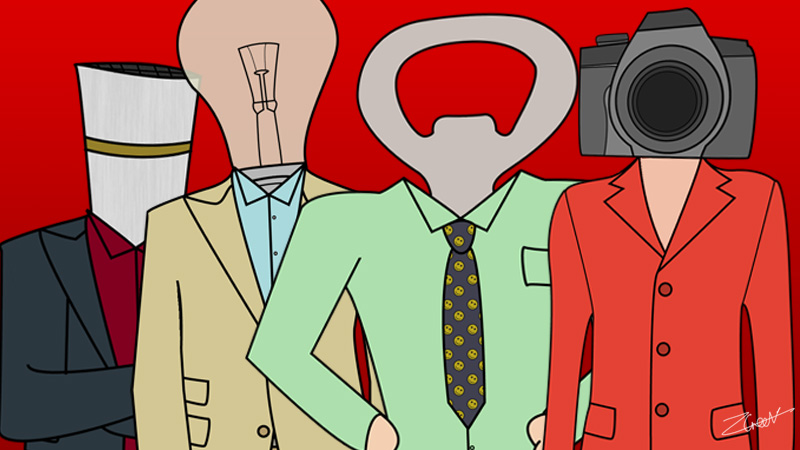

Your Face is a Saxophone is a surrealist satire of the advertising industry, which makes fun of actual companies and brands. It tells the story of the staff of Buzzword Marketing, and their dealings with the absurd demands of their corporate clients. Also, everybody has inanimate objects instead of heads for some reason. It’s either an artistic statement on how consumerism objectifies us all, or an excuse for us to not have to animate their mouths moving; you decide. As a bonus, Your Face is a Saxophone is Public Domain under CC0.

My friends and I formed a group called Plankhead to produce the series. At the beginning of 2011, we released the first full-length, 25 minute episode — a pilot that we pitched not to a TV network, but to the Internet. We were able to raise enough money from individual donors to make a second one, which came out astronomically better than the first. Naturally, we’d like to continue the series — we have five more episodes planned, and we’re starting on the third in the next few weeks. But this isn’t just yet another crowdfunded indie project.

Your Face is a Saxophone started out as an assault on advertising. Since it began, I’ve realized that the problems with advertising are just one part — along with the copyright monopoly, unchecked greed, the pursuit of censorship, and other problems — of the holistic problem that is the ancien régime of the corporate entertainment industry. Much like these motivations, Your Face is a Saxophone is a part of a larger whole; a prototype for how to produce, promote, and proliferate culture in complete opposition to the problematic habits of the copyright industry.

I certainly hope you find the show entertaining. But even if you don’t, let me explain why you should still help it succeed:

The Problems

Advertising

In conceiving the project, I decided I was fed up with advertising-supported media. Humanity had created the Internet — possibly the most empowering technology of the millennium — and yet had failed to come up with a better way of sustaining its contents than by splattering ads all over everything. At best, it’s annoying and ugly — São Paulo, Brazil mayor Gilberto Kassab famously called advertising “visual pollution” when banning billboards in 2006. At worst, advertising has a chilling effect on free speech, making it too unprofitable to say something that corporations disapprove of.

So, I decided to prove that a full-length TV show could be made without advertiser support — by making it something that nobody in their right mind would want to sponsor.

But how to finance a show without ad dollars? There’s grants, but that just gives the veto to governments or private foundations instead of corporations. No question: it would need to come from individual fans — the people who actually care about the message. So, that’s why we crowdfunded Episode 2 of Your Face is a Saxophone, and plan to continue that.

Obviously, crowdfunding alone can’t go very far; Mike Masnick reminds us often that “Give it away and pray” isn’t a business model. That’s why many independent creators make their money selling T-shirts, mugs, mousepads, posters, and other merchandise. Except that falls into the trap of…

Selling a Product

The chief reason why the copyright industry is running around with its head cut off is because its products — music, movies, news, information — are no longer products. Everything digitized can, and will, be made available for free, regardless of its creator’s wishes. You can’t sell a non-scarce good.

Obviously, many companies and artists still try this by “selling” digital downloads. But it’s been said that the way to compete with piracy is to respect your customers; selling a glass of tap water is not respectful to your customers.

Whereas the old guard tries to recreate the scarcity of information by lobbying to destroy our civil liberties, more nimble independent players simply find new scarcities to sell. This often takes the form of merchandising, which the copyright industry does its fair share of as well.

But that runs into another problem: everything can, and will, be digitized. Why buy an official T-shirt, poster, mug, or mousepad when you can print your own? 3D printers are set to drop in cost, increase in capability, and pervade society through the next decade, making the sales of merchandise into a very short-sighted business plan.

Merchandising also alienates the audience, reinforcing the false dichotomy of producer and consumer. It turns the art into yet another advertisement, and the fans into nothing but customers for the mass-produced crap which the art is hawking. Speaking of which…

Monologue Culture

When you hear the term “consumerism” thrown around, you often think of what I just alluded to: people being sold a bunch of crap in massive quantities. But the copyright industry fosters another type of consumerism: the consumption of monologues.

Most media takes the form of a creator or author communicating a message to the audience. The audience’s response, input, or thoughts do not matter, because they can’t change the message. This isn’t inherently a bad thing — indeed, it’s often a good thing for one person’s message to be communicated without meddling from others. The problem is that the audience doesn’t feel invested in the message. It doesn’t feel like it’s theirs.

The works which foster large, devoted fanbases are the ones which capture an audience’s imagination. A well-built fantasy world will inspire thousands of fan-fiction spinoffs; a great piece of music will inspire thousands of cover performances; a video game is already more engaging simply because it’s interactive, but open, hackable code will inspire thousands of modifications. Works like these do get the audience invested, and give them a sense of ownership.

This creates two challenges. First, not every story worth telling, song worth performing, or creation worth creating has the capacity to inspire direct remixing; Hitchcock’s Psycho isn’t the most fertile ground for a fan-fiction movement, for example. That point, I’d like to get back to. For now, let me digress with the second challenge: the fact that the copyright industry makes such creative communities illegal.

Creative Monopolies

Through use of the copyright monopoly, the industry acts as an oppressive creator’s guild. If you’re not a member of their inner circle, they don’t want you to be creating anything. They can achieve this because there is no such thing as “originality” in creative work; everything is based on, built on, or inspired by something that came before. Sometimes, the best new work comes from directly appropriating the past.

This is what makes the copyright monopoly so powerful. Hollywood can license a soundtrack of popular music, but an independent filmmaker cannot. Live performance venues cannot exist without paying licensing fees to the Big Three record companies, just in case a performer does something that might intersect with a copyright. Spinoffs and sequels to stories are the exclusive domain of the original publisher, and fan-fiction is regularly intimidated or sued out of existence. These are just a few examples of the hundreds of ways in which copyright monopolies are used to financially repress artists outside of the guild.

The attacks on civil liberties by the copyright industry aren’t about irrational fears of piracy or lost sales. The executives in charge aren’t that stupid; they’re well aware that the entertainment industry is growing, not shrinking. It is chiefly about stifling competition from the masses themselves. They fear that if we can meet all of our entertainment needs with YouTube videos, independent music, local art communities, and other such things, then we’ll no longer want to watch their TV and movies, listen to their music, read their books, or play their games. And they’re right. As Clay Shirky said in his legendary TED Talk, “Time Warner has called, and they want us all back on the couch, just consuming, not producing, not sharing. And we should say no.”

The problem is, having entrenched themselves and stifled competition for over a century, the copyright industry has our work cut out for us.

Nowhere Else To Go

While I was drafting this post, Paul M. Davis of Shareable happened to put out an article describing many of my concerns. Davis is ambivalent towards Techdirt’s Sky is Rising infographic, and writes:

For the truly DIY — the creators with limited resources who live precarious lives to pursue their passions while navigating an ever-changing media landscape — the effect of the Internet is far more complex than optimistic infographics and studies often suggest.

[A]s traditional sources of industry support (promotion, distribution, and simple business admin) crumble, it can take longer for indie artists to reach the critical mass of audience awareness to quit their day jobs. In the meantime, the workload for creators has increased, until they begin consistently making enough money to hire others to handle the additional labor that the Internet adds to the equation.

It’s unquestionably a good thing that the Internet is dismantling the copyright industry’s distribution monopoly, but its promise of eliminating their stranglehold on promotion hasn’t been fully realized. Before the Internet, creative people had to play the lottery, hoping that a corporate agent would notice them and scoop them up. Now, creative people still have to play the lottery, hoping that somebody with a large social network will notice them and tweet a link to their website. The odds may be better, but it’s still a raw deal.

The notion that artists need to work a day job until they one day “make it” is a tragedy, not a desirable component of a healthy society. As I’ve touched on previously, distracting people by forcing them to worry about meeting their basic needs holds back human progress. The copyright industry has done a poor job of solving this problem, but thus far, so has the Internet. As Davis says, DIY promotion for an unknown artist is still absurdly difficult.

I’ve witnessed this firsthand, in fact. The second episode of Your Face is a Saxophone was released at the end of October 2011. The reason you’re seeing this article months later is because working full-time on its production bankrupted me. When I said we’d raised enough money to make the episode, I was referring to buying new equipment — there wasn’t much left over to cover anybody’s cost of living. While finding and keeping a day job, I neglected to open-source the assets and project files, enact a promotional strategy, finish subtitling the new episode, or do much of anything that I’d needed to. Being unable to pay one’s bills is, as you can imagine, very distracting.

The Solution

It’s these problems that we’d like to tackle with Your Face is a Saxophone, using it to lay the groundwork for a new creative culture. Others may have pioneered the bits and pieces I’m about to describe, but it’s time to put them together in a cohesive, intentional whole.

Free and Open Source

Your Face is a Saxophone is CC0 Public Domain. Once an episode is finished and released, it belongs to the commons, irrevocably. We wouldn’t be able to enforce any copyright monopoly on it even if we someday lost our minds and wanted to.

Furthermore, it will be entirely open source. All art assets, audio, project files, and (if feasible) renders will be made available to the public. We’ll use as many open formats as possible (sadly, I haven’t had the time to learn Blender, so the first two episodes’ project files are in the propirateary (that’s not a typo) Apple Motion 5 format).

We won’t use creative monopolies, and through open source, we’ll chip away at the monologue culture problem. To further attack that…

Selling a Process

As my experiment in impromptu filmmaking shows, people enjoy creating things — and it’s not just self-described “artists” who find the creative process to be just as entertaining, if not more, than experiencing the final product. This is why video games which spark people’s creativity — for example, anything that Will Wright has ever been tangentially involved with — have proved to be so massively popular.

But not every message worth communicating can be expressed in an interactive medium. There will always be a place for monologue media — for immutable text, sound, or imagery comprised solely of the vision of its author(s). That’s why we need to blur the line between audience and author, consumer and producer, by bringing the fans into the creative process.

We can’t — and shouldn’t — finance Your Face is a Saxophone by selling access to the finished episodes. Instead, we sell access to the community. Everyone who contributes any amount of money to Your Face is a Saxophone becomes a producer of the show.

To describe what that means, here’s an excerpt of an email I sent to current producers a couple weeks ago:

Though Plankhead does provide entertaining things to the world, it’s not — as people who wear suits and have far too high incomes would say — our “core business”. We don’t aim to sustain ourselves (or, in suit-speak, “make money”) by saying to people, “You are the audience”. We do that by saying, “You are the artist”.

If you’re receiving this email, then you were instrumental in the creation of Your Face is a Saxophone. That makes you an artist, because you brought art into being. You’re all artists. Guilty as charged.

And you know how else you’re all artists? Have you ever heard a song, and then hummed it to yourself in your head for hours and hours afterwards? Have you ever quoted a movie to your friends? Ever gone halfway through a terrible pun, put on sunglasses, finished it, and then screamed YEAAAAAAHHHHH? Those are all creative acts. Even if you didn’t make up any original words or sounds, performance — even if nobody’s watching — is creative. You’re all artists.

Everyone has that burning drive to create. Some people have it during urination; they should probably see their doctors and get tested. For everyone else, Plankhead is here to help.

Enough of this abstracty mumbo-jumbo. Let’s talk concrete stuff:

For Episode 3 of Your Face is a Saxophone, we’re going to keep you updated, every step of the way, with production. And you know what I want you to do? Respond. Make comments. Make suggestions. Throw us ideas. Help us create this thing. If you think something should be animated differently, let us know. If you think there’s a hilarious prop missing from a background, tell us. Maybe you can even draw it for us and we’ll put it in. If you think Dave needs to re-record a line because he’s not making Blake sound enough like an adorable idiot, say so. Be a part of the process.

We’ll be putting up wikis and forums and stuff to make this kind of thing easier, but also suggest ideas for how we can share the production process, and get your input. Help us create the creative process.

For future episodes, we’ll also be letting you into the writer’s room. I’ve only written the scripts up until Episode 3, so I’m going to need everyone’s help to flesh out the stories for the remaining four episodes.

YFIAS isn’t just a prototype of a new way to finance art. It’s also a prototype of a new way to create it: having the community involved every step of the way, blurring the line between fan and creator.

This will effectively make our revenue stream completely indifferent to file-sharing. It won’t even be possible to lose a “sale” to a free download, and we’ll be able to brag that we have a 0% piracy rate.

For-Progress, Not For-Profit

We reject the notion that art is an investment that needs to be recouped. It is a desirable end in and of itself. The copyright industry views art as an incidental logistical concern on the path to making money; if they believed they could make more money selling toilet paper, they’d do it. This is the root of the problems that they cause.

I’m not seeking personal financial gain from Your Face is a Saxophone; my cost of living just happens to be a necessary expense of the project. And I’d wager that most artists feel exactly the same way about their work.

We’ll use the success of Your Face is a Saxophone to build Plankhead, our organization, into a support network for artists. A cooperative media company, owned and operated by its creative workers. Were I pitching it to a Silicon Valley venture capitalist — people who like to hear things like “it’s an AirBnb for Facebook games” or whatever — I’d call it “a Mondragon for media”. When we get to that stage, we will promote any work in any medium that is A) technically competent and B) willing to be released under CC0 — and finance it if possible. We’ll do our best to keep personal taste out of the vetting process, because all art has a right to exist.

Ultimately, the goal is not to make artists fabulously wealthy; it’s to keep them fed and clothed so that they can concentrate on creating things.

How You Can Help

To make this happen, we need producers and volunteers.

Today, I’m setting a new fundraising goal of $3000. That amount of money would allow me to devote my full time to animating the third episode for three or four months. If we raise even more than that, we might be able to add a second or third animator to speed the process along. You can contribute and become a producer through our donation page.

We also need people who can help produce, promote, and proliferate the show. A comprehensive list is on our volunteering page, but a few examples include:

- Subtitle translators

- Torrent seeders

- Social network/blog promoters

- Web technicians/designers

- Python coders who can figure out how to automate the “lip”-sync animation so that we can switch to Blender already (or anyone who can help us switch to Blender in any way, for that matter)

People who make significant volunteer contributions will probably get producer status out of the deal.

Ultimately, we need you to help us prove that this works. Let’s give the world hard, concrete evidence that even a traditional TV-length show with no copyright protection whatsoever can be successful. Let’s show that we don’t need to create a false pretense of buying and selling digital “goods” to sustain artists. Let’s validate the idea that art for art’s sake is something that society values, believes in, and wants to exist.

Hey. I love that you use Universal Subtitles to subtitle the episodes! But then you should also actually embed the US versions of the videos on your website. Just go to each episodes page on US and you will see an embed code.

The reason I haven’t is because I’ve mirrored the subtitles on YouTube’s built-in captioning system. Although that system bugs me, because I have no idea whether it automatically activates based on a user’s language setting.

I do need to redesign the Watch page so that videos pop up in a larger lightbox (instead of the tiny 500-pixel column, because you know there are some people who’ve never heard of the Full Screen button), so I’ll probably incorporate US and Vimeo into that.

Cool! Remember that it’s not just about the subtitles being there, but also that the US sutbibltes are actually text that can be used “read” by different kinds of tools, used for example by deaf people. 🙂

Ahh, right, I forgot about that part. I know the transcript affects YouTube search results (funny story, actually: about half the hits on Episode 1 were because the plot point about Pepsi caused it to show up as a “Related Video” to a Pepsi commercial — thanks to the subtitles), but I suppose that doesn’t carry over to embeds.

I’m very pleased that Universal Subtitles is used and expressed here. I’m the manager of Universal Subtitles Deaf/HOH department. We’re all for the people in every country. Feel free to visit universalsubtitles.org.

There seems to be a lot of talk these days about the real threat to Big Media being “amateur” creation, as opposed to piracy. I wrote about it myself actually — shameless plug: http://my.opera.com/free_culture/blog/2012/01/28/after-the-war-on-sharing-comes-the-war-on-creating — and why I focus on creation that takes less investment, we appear to be in agreement.

Oh, and that article on Shareable was slammed in the comments over the little entitlement issue. 🙂

Well, to be fair, you slammed it in the comments thread over an entitlement issue. And the Left 4 Dead fan-film you described in your piece as “a bunch of friends having fun together” was actually sponsored by three different online stores, produced by this production company, and had a crew of over 30 people.

See, this is the problem: our movement has been focusing so much on the idea that Big Media feels too entitled to profit from its investments, and making dubious arguments that “friends having fun” will give us a perfectly adequate amount of culture. We forget the other problem that Big Media has (partially) created: the fact that barriers to creativity aren’t a good thing.

You’re right, in your comment over there, that 90% of everything is crap — that is, 90% of everything that ends up getting created. 10% of everything not created because the author couldn’t get the money, didn’t have the willpower to work seven jobs, or whatever, would not have been crap had it been given the chance to exist.

We pirates have been using these talking points about how life has been historically hard for artists, and that didn’t stop anyone. Except it did stop quite a few people. It stops people every single day, because they have to shift their focus to doing work which may or may not contribute anything to society, just so they can eat at the end of the day.

Yes, a few lucky people manage to pull through here and there, but you know what? That’s not good enough. This is the same 99%/1% problem that’s been sparking popular uprisings across the world. People are realizing that “work hard and maybe you’ll win the lottery and be in the 1%” is a terrible way to structure a society. It’s not an entitlement issue, it’s an issue of shit making sense.

So that’s why I’m asking that we put our money, our labor, and our efforts where our mouths are. We say that we care about artists, and our political opponents don’t believe us. Let’s prove them wrong. Let’s prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that we can make the world better for artists than they can.

Did you ever notice the second comment on that post? I would never have mentioned it if mine was the only one. And you’re being facetious, right here:

“90% of everything is crap — that is, 90% of everything that ends up getting created. 10% of everything not created (…) would not have been crap had it been given the chance to exist.”

Really? What about the 10% that *does* end up being created and *is* excellent? Seriously, what kind of math was that?

The second comment was someone replying telling you you’re full of shit. And do you even know the meaning of the word facetious because the way you used it makes no sense. In fact that whole paragraph makes no sense.

Zacq was trying to be nice to you but I’m just gonna come out and say it, it’s pirates like you who make us all look bad. You have no idea what you’re talking about.

Hey, I jumped onto your torrenting both to watch the craziness but also to help with the distribution. However, there doesn’t appear to be a 100% seeder atm =

Ha ha, uhhhhh, yeah, that’s why we need help. I just started seeding it again, so maybe it’ll work now.

Torrent for Episode 2 will be coming as soon as I finish the subtitles for it, by the way.

That changed rather quickly. Thanks! =D

I love Your Face is a Saxophone and the idea of this cooperative content firm and I’m more than happy to support it. This is exactly the sort of innovative thinking that should be happening across all sorts of industries. I was a tiny bit dismayed that your excellent post didn’t mention your Flattr account as a great way to support perhaps you an add a link to that at the end. Keep up the great work and I wish you the best success perhaps I’ll find a minute to help out on the social media or blogging side.

your fan,

~Evan

Why thank you!

I didn’t call special attention to Flattr because I didn’t want to have to devote another paragraph to all the payment methods you can use. But perhaps adding a link at the end is a good idea. I’ll add that tomorrow sometime.

Thank you Zacquary,

Flattr fits perfectly with your philosophy, oh and also lots of folks who read or write on Infopolicy use it. 😉

Okay, you convinced me.

I’m going to translate subtitles into Czech.

I can help also with pictures (Both PS and Illustrator)

I’m gonna support this.