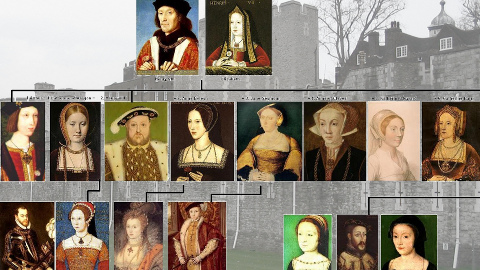

On May 23, Mary was formally declared a bastard by the archbishop. Her mother, Catherine, who was a catholic and the Pope’s protegé, had been thrown out of the family by her father Henry, who had turned protestant just to get rid of Catherine. This was an injustice Mary would attempt to correct all her life.

The King Henry VIII wanted a son to inherit the Throne of England for the Tudor dynasty, but his marriage was a disappointment. His wife, Catherine of Aragon, had only born him a daughter, Mary. Worse still, the Pope would not let him divorce Catherine in the hope of finding someone else to bear him a son.

Henry’s solution was quite drastic, effective and novel. He converted all of England into Protestantism, founding the Church of England, in order to deny the Pope any influence over his marriage. Henry then had his marriage with Catherine of Aragon declared void on May 23, 1533, after which he went on to marry several other women in sequence. He had a second daughter with his second wife, and finally a son with his third wife. Unlike the bastard child Mary, her younger half-siblings — Elizabeth and Edward — were protestants.

Edward succeeded Henry VIII on the throne in 1547, at the age of nine. He died before reaching adult age. Mary was next in the line of succession, despite having been declared a bastard. Thus, the outcast ascended to the Throne of England with a vengeance as Mary I in 1553.

She had not spoken to her father for years and years. Rather, hers was the mission to undo her father’s wrongdoings to the Faith, to England, and to her mother, and to turn England back into Catholicism. She persecuted protestants relentlessly, publicly executing several hundred, earning her the nickname Bloody Mary.

She shared the concern of the Catholic Church over the printing press. The public’s ability to quickly distribute information en masse was dangerous to her ambitions to restore Catholicism, in particular their ability to distribute heretic material. (Political material, in this day and age, was not distinguishable from religious material.) Seeing how France had failed miserably in banning the printing press, even under threat of hanging, she realized another solution was needed. One that involved the printing industry in a way that would benefit them as well.

She devised a monopoly where the London printing guild would get a complete monopoly on all printing in England, in exchange for her censors determining what was fit to print beforehand. It was a very lucrative monopoly for the guild, who would be working hard to maintain the monopoly and the favor of the Queen’s censors. This merger of corporate and governmental powers turned out to be effective in suppressing free speech and political-religious dissent.

The monopoly was awarded to the London Company of Stationers on May 4, 1557. It was called copyright.

It was widely successful as a censorship instrument. Working with the industry to suppress free speech worked, in contrast to the French attempt in the earlier 1500s to ban all printing by decree. The Stationers worked as a private censorship bureau, burning unlicensed books, impounding or destroying monopoly-infringing printing presses, and denying politically unsuitable material the light of day. Only in doubtful cases did they care to consult the Queen’s censors for advice on what was allowed and what was not. Mostly, it was quite apparent after a few initial consultations.

There was obviously a lust for reading, and the monopoly was very lucrative for the Stationers. As long as nothing politically destabilizing was in circulation, the common people were allowed their entertainment. It was a win-win for the repressive Queen and for the Stationers with a lucrative monopoly on their hands.

Mary I died just one year later, on November 17, 1558. She was succeeded by her protestant half-sister Elizabeth, who went on to become Elizabeth I and one of the highest-regarded regents of England ever. Mary’s attempts to restore Catholicism to England had failed. Her invention of copyright, however, survives to this day.

Next: The copyright battles begin, with victories for both sides.

Previous: The Black Death decimates scribecraft.

Primary sources: Wikipedia entries for Mary I and Stationers’ Company, and Question Copyright.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Piratpartiet and Falkvinge, Falkvinge. Falkvinge said: The monopoly was awarded to the London Company of Stationers on May 4, 1557. It was called "copyright". http://is.gd/U1gAud #incfopolicy […]

Still waiting for how this is relevant to Piratpartiet. Printing your own books, making your own movies or music is one thing, it is a different thing althogether to take the right to read, watch or listen to something without paying for it. We don’t need the copyrighted material for democracy to function (C’mon – American Pie! Brittney Spears!), so why does your party think that we should have the right to that material – without paying?

That’s a very dishonest illegitimate and false question, since it is based on completely false premisses, that reverses the order of how society works, and it is therefore a question that no one should even try to answer in the format is it asked.

Allow me to educate you on why it is dishonest.

Society doesn’t start with a natural state where everything is forbidden for citizens, until it is specifically permitted.

Society works the in complete opposite order. Everything is allowed for citizens, until it is specifically forbidden in legitimate legislation.

No citizen should be forced to motivate or provide burden of proof regarding why he shouldn’t be forbidden by legislation to be able to freely perform certain possible actions.

The only thing that should be motivated is why something should be legislatively forbidden, and all burden of proof for that task falls on the interested party that wants something to be forbidden, usually the legislator, or in this case anti-pirates, creators or rights holders.

So the real question, and the only question that an honest person should ask, and definitely the only question anyone should try to answer, is why filesharing should be forbidden in the first place.

Why should people not be allowed to create their own physical copies, with their own physical property, that they themselves own?

When an anti-pirate tries to answer that question, there are certain rules that applies, since it is a legislative outcome one tries to motivate.

Rule one(and i’m gonna skip rule 2 and 3 for now, since no one has ever gotten past rule 1), is that first of all one must provide actual proof, that points to that an actual measurable problem with intellectual works even exists, in this case with the goal of economical copyright, and that filesharing leads to lesser cultural maximization for society, if the creator or later rights holders isn’t privileged with a monopoly over non-profit distribution and manufacturing of physical copies.

Any claims that creator’s or later right holders should be privileged with such a monopoly out of principle or fairness, just because they created the works, is way of line, since the economical parts of copyright in no way exists out of principle or fairness.

Any proof put forward that a certain industry or individual, that tries to make profit from a certain individual business model, among many different available ones that are based around the use of intellectual works, in this case manufacturing, distributing and selling physical copies to consumers, any proof put forward indicating that that particular industry or business model can’t co-exist along side free filesharing, is alone completely irrelevant from a economical copyright point of view.

No one has been able during the last 40 years to produce any sort of evidence that holds up to scrutiny, that shows that an actual problem related to the concept of economical copyright exists, related to consumers non-profit manufacturing and distributing of physical copies for personal use, and that any form of legitimate legislation can forbid such actions.

Therefore filesharing is not a problem.

There’s nothing illegitimate with filesharing.

Filesharing is a completely legitimate action.

People can fileshare published culture as much as they want, for whatever reason they choose, and there’s nothing wrong with it.

No filesharer should ever try to legitimize why they fileshare.

Anyone who doesn’t accepts or understands this, but instead tries to fabricate false premisses on how society works, by putting forward false questions that reverses the burden of proof, only proves that he either doesn’t know the first thing about copyright, what it is, or why it exists, or that he doesn’t know the first thing about participating in an actual debate, by producing legitimate honest questions or arguments, without resorting to false Ad Hominem-arguments.

So the only response to your question is, don’t you know what copyright is, don’t you know how society or legitimate legislation works, or don’t you know how to participate in an actual debate?

You should never have asked your question in the first place. Please try to learn why, and what’s wrong with it, so you don’t repeat it.

Too intellectual Fredrika – the simple, simple, simple answer is just that the technology has passed it by. End of. Copyright now is like a law making it illegal for the sun to rise (what RIGHT has the sun to rise, BTW?)

Basically what you are saying is that you can come into my home and eat my food because I haven’t said that you can’t?

Besides – your rant has nothing at all to do with Rick’s post which was about the right to print books. (The right to print, not to read)

You’re the only one saying that. If we could eat the data we copy, why would anyone care about your pop tarts?

“The right to print, not to read.” There are no laws against reading, last time I checked.

Wat a bloody rant! ( 😉 )

Why should people not be allowed to create their own physical copies, with their own physical property, that they themselves own?

Noone has questioned that. The queation is why you can take the right to watch, listen or read something that you do not own. “Democraci” is an answe that might have worked in the 19th or 20th century, but it does not work today.

Should we have the ‘right’…? An interesting philosopical question. The point is, we have the ability – anybody want some ‘American Pie’? Just click here http://thepiratebay.org/search/american%20pie/0/99/0

No? In your example the physical property belongs to you. In the example with filesharing the physical property belongs to the filesharer.

The correct question is why shouldn’t the filesharer be allowed to do what he wishes with his own physical property.

The filesharer shouldn’t have to make an excuse or answer a question regarding why he should be allowed to do what he want’s with his own property.

It’s the other way around, someone else should motivate why he shouldn’t be allowed to.

As you can see, my post was an answer to a previous comment, no to Rick’s post.

And Rick’s post wasn’t about the right to print books, Ricks post was about the opposite, forbidding others to print books. You make the exact same mistake as Sven, you try reverse the order of society, with false fabricated premisses.

People don’t need permission to do things with their own physical property, they are allowed to do with it as the wish, until it is forbidden in legitimate legislation.

That’s the practical function of copyright, forbidding others to manufacture physical copies, that they can create with their own physical property.

Ooh, but someone has, that’s what the entire filesharing debate is all about, that people shouldn’t be allowed to create their own physical copies, with their own physical property, that they own.

And again, that question is false and reversed. You don’t need permission or the right, to watch, listen or read something, that you have in your own possession, or that you yourself own? Once you have a physical copy in your possession, you can freely watch, listen or read it as much as you like.

Or you’re a bit confused over who owns what? You can only own physical property, including physical copies of intellectual work, and all property involved in filesharing is owned by the filesharers.

The fact than one can be the rights holder to a monopoly over distributing and manufacturing of physical copies is not the same thing as that someone owns something. You can not own intellectual property or copyrighted works.

@Pia

“The queation is why you can take the right to watch, listen or read something that you do not own. “Democraci” is an answe that might have worked in the 19th or 20th century, but it does not work today”.

You dismiss democracy but still claim to be moral and have a moral objection to file sharing ….

Technology has made “distributor” business in most senses useless. If the goal of market is to allow for competition and ever growing effectiveness of businesses – then businesses requiring “competing with free”-legislations should rather be punished than encouraged by law.

The “free” parts of businesses are signs of work that is no longer needed to be paid for. In this case distribution of immateria. People do it for free in their spare time, does not require anyone to do any actual paid “work” for the distribution to go on. Don’t get me wrong that I’m proposing that the CREATION of immateria does not have any value any longer. That is perhaps the ONLY part of the business still having any value. Losing the record companies won’t be a big loss. We still have the creators there, if we just are willing to pay them for THEIR work.

There are so many examples in history where the conservative actors of various businesses strive to hold back the usage of new technology by their competitors. This is just one of very many such.

[…] death penalty hadn’t worked, Queen Mary I needed an ally within the printing industry. She awarded a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, in return […]

[…] Part 2: Bloody Mary […]

[…] Izvor http://falkvinge.net/2011/02/02/history-of-copyright-part-2-tudoric-feud/ […]

[…] Previous: A Vengeful Daughter Creates Censorship. […]

[…] tako željnem prostem trgu. V njem opozori, da je institut ‘varovanja avtorskih pravic‘ bil vzpostavljen 4. maja 1557 v namen cenzure političnega disidentstva, ter opravi s smešnim argumentom o prepotrebni […]

[…] sotto la Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione – Non commerciale 2.5 Italia. (Traduzione). Originale inglese di Rick Falkvinge in pubblico dominio. Tweet TAGS » Cultura e memoria […]

[…] Next: England and a vengeful daughter. […]

[…] the Enlightenment [insert sunset and kittens here], referring to the Statute of Anne in 1709, which wasn’t the first copyright anyway. In reality, the neighboring-rights monopolies were created in fascist […]

[…] Fuente de la nota […]

[…] in force in the United Kingdom, and pretty much the United Kingdom alone (where they were enacted in 1557). You know the “Made in Country X” that is printed or engraved on pretty much all our […]

[…] zeal to protect the rights of creators to the fruits of their efforts. When the copyright monopoly was first created on May 4, 1557, it was a means of censorship of political dissent. Nobody at the time thought to […]

[…] History of copyright, part 2: Bloody Mary (en español) […]

[…] History of copyright, part 2: Bloody Mary (en español) […]

[…] original copyright monopoly, which was enacted by Queen Mary I on May 4, 1557, was created as a repressive tool against freedom of speech in order […]

[…] guild couldn’t get the copyright monopoly reinstated, the lucrative monopoly that had previously been a censorship regime. Importantly, they didn’t argue that nothing would get created […]

[…] original copyright monopoly, which was enacted by Queen Mary I on May 4, 1557, was created as a repressive tool against freedom of speech in order […]

[…] original copyright monopoly, which was enacted by Queen Mary I on May 4, 1557, was created as a repressive tool against freedom of speech in order […]

[…] nie zostałaby wydrukowana i rozpowszechniona, gdyby gildia wydawców nie otrzymała monopolu, który wcześniej służył cenzurze. Co ważne: nie twierdzili, że nic nie zostałoby stworzone bez monopolu, mówili tylko, że nie […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly gave […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly gave […]

[…] work, commercial incentives to kill freedom of speech worked flawlessly. Mary I of England gave a printing monopoly to London’s printing guild, the London Company of Stationers, on May 4, 1557. This monopoly gave […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] ја краљица Марија I створила монопол на ауторска права 4. маја 1557. то је био пунокрвни механизам у служби цензуре: […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Queen Mary I created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557, it was a purebred censorship mechanism: in exchange for a lucrative monopoly on printing, the […]

[…] Rick Falkvinge reported last year, Queen Mary, the first, created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557. According to research from Falkvinge, it was initially created as a censorship […]

[…] Rick Falkvinge reported last year, Queen Mary, the first, created the copyright monopoly on May 4, 1557. According to research from Falkvinge, it was initially created as a censorship […]

[…] History of copyright, part 2: Bloody Mary (en español) […]