What would a truly free-market approach to copyrights and patents look like?

The problem we have right now is this:

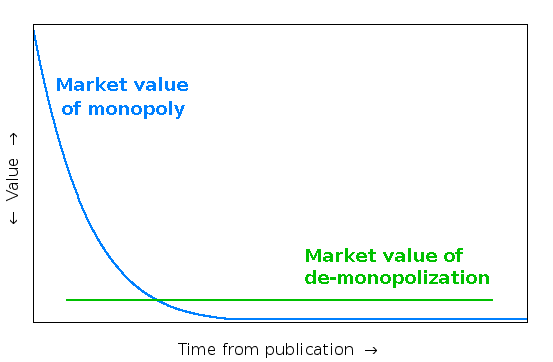

The flat green line represents the value to the public of de-monopolizing the work — think of it as “what the public would be willing to pay for unrestricted access”. The point where the curved blue slope crosses the green line is the point where there is no longer any public or private purpose to having a monopoly. From that moment on, the value of the monopoly to the rights-owner is equal to or less than the value of de-monopolization. Yet today, the monopoly continues beyond that point. The green line is simply ignored in the current system: we pretend it does not exist.

(The graph is a simplification, but not in ways that matter to this proposal.)

You might think there’s already a market solution. After all, in the current system, anyone could in theory be offered a fixed sum to liberate their work into the public domain [1]. But markets don’t quite work the way we’d hope. This is is why we have eminent domain in real property, for example. As soon as someone starts talking about building an airport in some farm fields, all of a sudden every farmer decides their field is worth ten times as much as it was the day before, such that no airports could ever be built if we did not use the pre-rumor valuations. It is the same with copyrights and patents: the mere expression of interest in re-use drives up the price instantly, and the perpetual optimism of rights-holders ends up stretching their monopoly past its natural market end — hurting everyone else and preventing further re-use, yet frequently without realizing the benefit the rights-holder hoped for. We all lose.

But unlike with land, there’s a way out, because there’s a third thing we can do besides sell or not sell: we can liberate. That makes all the difference.

The Declared Value system

Suppose things worked this way instead — I’ll use copyrights for the sake of discussion, but this applies to patents too:

A new work gets an initial automatic copyright term, as it does today but much shorter: maybe a few weeks or months from publication, enough to ensure there’s time for the owner to register the work if they wish to extend the monopoly.

If the copyright owner does not register, the work simply enters the public domain [2].

But there’s an alternative: instead of letting the monopoly lapse, the copyright owner can choose to register the work for continuation of copyright (renewable annually), with a registration fee proportional to the self-declared value of the work. That is, the copyright owner picks a number of dollars (yuan, euros, whatever) that she claims the work is worth. It can be any number at all, but the yearly registration fee will be a percentage of it — for discussion’s sake, say 1%. The exact proportions don’t matter here: it could be 0.5% or 2% instead of 1%, registration could be semi-yearly instead of yearly, etc. The idea is the same, regardless of how you set the knobs.

Now comes the key:

Since that declared value is now a matter of public record, anyone can pay it to the copyright owner to liberate the work into the public domain. This is not a purchase, it is a liberation. Prior to liberation — whether it comes through payment or through term expiration — people would still be free to sell or lease their copyrights, for whatever price they can get (which, interestingly, may be higher or lower than the registered value — the market dynamics behind that decision are just as rich as those involved in determining exclusivity value under today’s copyright system). But whoever the owner is, whether the author or someone else, they’re responsible for keeping up the registration. And while the work is still under registration, anyone can come along and pay the registered owner the declared value to liberate it.

Liberation, unlike purchase or lease, is a mandatory transaction. The justification is that since the registrant chose the price in the first place, it is by definition fair: it was self-declared. Furthermore, these are after all public monopolies, and the public’s ultimate interest is in having works be available without restriction. For governments to hand out monopolies with no escape clause has always been an abdication of responsibility. If there is a way to fix that, we should take it.

The copyright holder has an incentive not to declare too high a value, because she’ll have to pay a percentage of it to register; she has an incentive not to declare too low, because then someone will come along and liberate the work very quickly at a low price (though some artists will find that liberation is economically a better deal for them anyway, and simply not register, or register at a declared value of zero in order to get a timestamp for attribution purposes).

Because the value of a work may change over time, the registrant may adjust the declared value up or down each year when renewing the registration [3]. This is also one of the reasons behind that brief initial registration-free monopoly term: it gives the copyright holder a chance to judge the work’s monopoly value, information she can use to decide how much to register the work for.

Whether indefinite renewal should be available is an open question. Personally I think not, for two reasons: first, because there has simply never been a compelling argument for perpetual copyright and most jurisdictions do not have it. Second, because awareness of an approaching horizon will pressure registrants to set lower liberation prices as that horizon comes closer — which is the right direction for things to move, from the public’s point of view, since even the most confident authors cannot reliably predict years ahead of time which monopolies will remain valuable, and therefore far-future valuations do not have a significant incentivizing effect anyway.

But even if indefinite renewal were permitted, the system still has desirable effects. The tendency of monopolies to accumulate in media conglomerates (who then press for Internet censorship to preserve those monopolies) would be greatly lessened by the cost of maintaining all those registrations. Forced to choose which assets are really valuable, the companies would have to lower the liberation values for many works, thus providing the fertile ground for re-use and innovation that artists, other publishers, and the rest of us are denied under the current system.

On “Balance”

While this proposal is a compromise, it’s at least a compromise tilted toward the public interest. By analogy, think of a homeowner who cuts a driveway opening onto a public street in order to gain access to a private garage. If I take a streetside parking space away from the public, I expect to pay the city (that is, the public) a fee, and usually annually, too, not just a one-time fee. Similarly, a copyright owner who wants to keep a work out of the public domain should pay for that privilege. But unlike a garage, this privilege need not be permanent, because losing monopoly control over a work is not as serious as losing one’s indoor parking space.

This system would go a long way toward alleviating the orphan works problem, by ensuring that the copyright owner of a work could always be found (someone must be paying the fees over at the registry), and toward alleviating the ghost works problem (in which derivative works are suppressed), by setting a maximum amount of money that, in the age of Kickstarter, would usually still be attainable by a motivated party who wanted to see that work in the public domain.

The copyright lobby frequently talks of finding an appropriate “balance” between the needs of creators and the needs of the public. Like many appeals to balance, it is a smokescreen for something else: in this case, for efforts to increase copyright terms and restrictions beyond their already absurd lengths. The “balance” they’re talking about neatly presupposes that creators and the public are somehow on opposite sides, while multinational content monopoly conglomerates are, curiously, absent from the picture altogether. (Their portrayal is also historically suspect, as copyright was primarily designed to subsidize distributors not creators anyway.)

Thanks to this focus on exclusivity-based balance, proposals to improve the system are usually minor tweaks: broader “fair use” rights, a more thorough prior-art discovery process, various changes in scope, etc. But these approaches leave the basic problem untouched: when a copyright or patent is granted today, it creates a monopoly with no countervailing pressure towards a true free market.

There needs to be a market-based representation of the value of de-monopolization, expressible by those whom de-monopolization benefits. In Macaulay’s famous words, “the effect of monopoly generally is to make articles scarce, to make them dear, and to make them bad.” [4] Anyone familiar with, for example, the mess George Lucas made of his monopoly on the “Star Wars” movies will instantly see Macaulay’s point. The problem is not that Lucas botched the sequels, but that the Lucasfilm monopoly prevents anyone else from doing better. This is the problem with monopolies generally — it’s not what they let the monopoly owner do, it’s what they don’t let others do. Monopolies are the opposite of free markets.

The Declared Value system introduces de-monopolization as a market force, without involving the government in pricing decisions, term-length calibrations, or other arbitrary regulatory judgements [5]. The system takes “balance” seriously: it gives the rights-holder a decisive role in setting a valuation and benefitting from it, but at the same time represents the public’s interest in not having works monopolized forever. Crucially, it avoids the need for complicated regulatory formulas, which would inevitably create a target surface for monopoly interests to aim lobbying power at. Instead, it gives the public a mechanism for representing its own interests directly, with the government limited to a bookkeeping role.

The proposal is not merely rhetorical. I would be delighted, if surprised, for it to receive legislative interest. But it is also meant to expand the range of the possible. Fiddling with copyright term lengths and improving the Patent Office’s processes feel good, but they are fundamentally repainting a burning barn. To get lasting improvement, we need to permanently reduce the “lobbyability” of the system as a whole. The Declared Value method is one way to do that [6], and to show that market-tempered monopoly is possible in principle. It’s high time these kinds of solutions were on the table.

References:

[1] I’m using terms like “public domain” loosely here. That term is usually used in copyright law, not patent law, but it’s easy to intuitively understand what it means for patents: that no one has a monopoly, that is, there is no one with the power to restrict usage.

[2] There should be nothing shocking about this: the public domain is the natural destination for works, and even most proponents of lengthening copyright and patent terms pay lip service to that goal. Furthermore, registration requirements used to be the norm if one wanted to hold any public monopoly. Indeed, the requirement for copyrights was only eliminated under the theory that insisting on registration gave advantage to corporations who had economies of scale to streamline the paperwork involved in filing — which was probably true, in the days before the Internet, but today registration would be as easy as uploading a file and receiving a digitally-signed timestamp.

[3] Alternatively, the owner could be allowed to adjust the declared value at any time (perhaps even as a reaction to liberation offers), with the provision that any upward adjustment would require immediate payment of the difference between the old and new registration fees. However, the public domain would probably be better served by simply allowing adjustment only at fixed intervals: if the owner of a work can’t figure out its market value and set the fee accordingly, that is no reason to favor the owner over the public when the work is being liberated at a price the owner clearly once thought sufficient.

[4] en.wikisource.org/wiki/Copyright_Law_(Macaulay)

[5] One of the problems with not having a systematized and predictable path to de-monopolization is that we instead get unpredictable decisions like India’s decision to set a compulsory license rate on a drug still under patent. The point is not that the Indian government made a mistake — the decision was quite defensible — but that handling each such instance as a special case inevitably leads to lack of predictability and, eventually, to corruption. Yet it’s governments that issue patent monopolies in the first place: if they can set compulsory license rates in specific cases, then they can offer a mechanism for de-monopolization in the general case.

[6] My colleague Nina Paley has suggested a simpler system: bring back registration, and set the fee for the first year at $1, the second year at $2, the third year at $4, then $8, $16, $32, $64, and so on. This has the advantage of immediate comprehensibility, and it’s clearly effective at tempering the monopoly: very few works would remain restricted past the 20 year mark, and her system doesn’t need to be adjusted for inflation for a long time.

[7] For works released under a free license, the fee should be waived, and indeed the requirement to register or renew at all should be waived, because such licenses are non-monopolistic by definition. For simplicity’s sake I did not mention this in the original proposal. Richard Stallman immediately noticed the problem; I thank him for pointing it out, as that reminded me to add this footnote.

While this does seem like an interesting proposal, there are a couple of points I’d like to ask questions about. Under this system, would it be possible for the initial registrant to sell rather than simply lease the rights to the work? You mention that the cost for a lease could potentially be higher than the value stated by the copyright owner, under what circumstances would this be the case? Lastly, this seems to me to disproportionately benefit the wealthy, the 1% if you will. A small time artist will not necessarily be able to afford a large value, even if they feel it would be worth more were they able to afford the mandated percentage. By contrast, large corporations like the MPAA et al would be able to afford large initial values, especially if they took the registration feel out of the royalties paid to the artists they sign as they currently do with massive distribution and breakage fees despite digital media having effectively no breakage and nearly zero distribution costs. What steps, if any, would be taken to protect content creators who choose not to sign with large companies, or do you believe the system should be completely laissez-faire?

It’s up to the current owner (that is, registrant) to decide whether they want to sell vs lease their monopoly, and under what terms. This proposal is simply about what form the monopoly itself takes.

One way to address the small artist vs big corporation issue you raise is to make the percentage not be a constant, but vary upward. In other words, smaller percentage when the total declared value is smaller, larger as the total declared value is larger. I’m not sure this is a good idea: a fixed percentage is easier to understand and easier for people to reason about. But this is another knob we could adjust if we wanted to.

Large corporations will always have an advantage when negotiating with individual artists (especially non-famous ones). This proposal can’t solve every problem in the world :-).

Certainly, it was just a couple of thoughts that had occurred to me as I read the article, I’m glad to hear your thoughts on possible solutions, however. Thanks for getting back to me.

How about a short, automatically-initiated period of copyright monopoly – say 5 years?

This would give artists time to find the best ways to monetize their works (people need money – it’s just a sad fact). It would also allow artists to enter their works into the market to find an appropriate ‘liberation value’.

Still, a period like 5 years would be short enough to have the public domain filled with modern works. I would be fine with having to pay to copy anything newer than 5 years, as long as I’m sure the actual artist gets an actual pay.

It would also be short enough to reduce the incentive to hyper-capitalize (I just made that up) on brand new works. If every investment into “Intellectual Property” would return value for a maximum of 5 years, the media industry would have much less to earn from raping their customers like today.

Yup — in fact, that’s what I proposed in the first version of this (coincidentally published five years ago). I discuss the reasons for the change of heart over in this other comment, but in short: I agree that a longer initial fee-free monopoly period is an obvious compromise to make.

It would be good if copyright did not cost anything. aNd thats a point.

I exposed this idea a few years ago in some mails.

There is an improvement to this idea:

1) the fees raised from the copyright/patent holders (an high fixed %) could be accumulated and used to buy some works. It could be used to match someone else money offered with a 1:1 ratio.

Surely this will still give extra power to those with more money, as the “little guy” with big ideas won’t be able to afford to pay the fee?

Example:

MegaCorp finds a cure for cancer and values it at €10billion. At 0.5% registration fee, it costs them €500million… something they might be able to afford. They register it and production starts.

Now what if (instead of MegaCorp), Joe Bloggs has been working at home for years and finds a cure for cancer and values it at €10billion. He cannot afford the €500m registration fee, so decides to sit on it until he can raise more money for a larger registration fee, which he might not ever be able to do. Note: Venture Capital would not work here, as they would ask for information about the product then likely rip him off; after all it wasn’t registered.

Maybe we would get lucky and Joe would accept that he can only afford €100,000 and register it for €2m, getting instantly liberated.

Maybe Joe wouldn’t even bother pursuing a line of research into curing cancer, knowing that he could never afford to register it for anywhere near its full worth. In effect creating a chilling effect against those without much money.

Basically, it prevents the small guy from creating and registering anything of significant value.

Do you know what a patent like that costs currently?

Replace “cure for cancer” with any other work, (e.g. blockbuster film) and the argument still holds true.

Basically, this system limits the amount anyone can make based on the amount of money they have. If someone poor comes up with a brilliant idea; they will not be able to exploit it commercially, but big cash-rich organisations will.

They can’t do it now either. On this very site is Christian Engstrom’s article on what a patent registration actually costs. And it’s very hard to get investments without registered patents. So you need to have money either way.

Actually, here you could extend the free period to, say, 5 years. Where all your registered works would be protected for free for full five years. And if you can’t make enough money to properly protect it in that time, then maybe your work isn’t worth as much as you think.

@SillyMe: Agreed; having an initial free period (even just one year) would prevent this problem, allowing a poorer person to go on to raise capital for the next year’s registration fee or sell the idea on to someone that can afford it 🙂

Nonsense. If the value is clear enough to put a 10M value on it, the creator can get a loan sufficient to cover the registration fee.

Sure, like someone is going to give out a €10m loan to a person with little to no money or collateral.

Besides, even if they would, the interest charges are still a cost/barrier to entry the super rich don’t have to pay/put up with under this system if there is no initial free period.

We simply cannot allow a system to come into place that prevents the poor from registering ideas. this is why the initial free period is integral to this idea working.

Interesting. This seems very closely related to my idea from February 2012 which I wrote about on my (quite inactive) blog. http://reengineeringtheworld.blogspot.fi/2012/02/taxing-intellectual-property-owners-of.html

Nice to see that someone else has come up with much the same solution. I take that as meaning I was on to something. I didn’t include the registration-free period, for instance, and my reasoning was a little different but the conclusions quite similar.

Interesting idea… I’ve also seen it in the context of inducing real estate property owners to self-disclose a fair estimate of their property value: you can declare what you want, but you must sell if offered (some fixed increment above) the value.

It also has parallels to ‘compulsory licenses’ at statutory rates… except the self-published rate is now for a ‘universal, perpetual public domain license’. And, like compulsory rates, the ‘declared value’ sets a rough cap (at least assuming the possibility of audience coordination) on total potential licensing revenues. So perhaps some blending of the ‘declared value’ and ‘compulsory license’ approaches would be possible, with the ‘declared value’ also helping to seed public licensing rates for uses less than a ‘universal, perpetual’ buyout.

Some correspondents seem to confuse Liberation – putting the work into the public domain – with a buy-out – the purchaser can profit from the acquisition. In the case of a buy-out the current owner would be allowed to bargain for the best price they could get.

In the event of a Liberation attempt, the owner/creator/developer should be notified and could be allowed a reasonable grace period in which to exercise the option of raising the declared value, provided they pay the non-refundable fee for one registration period.

One way to limit the duration of the monopoly would be to gradually raise the registration fee until the owner was no longer willing to pay it, rather than set an arbitrary time limit. This would fit especially well with an extended free period (e.g. five years) after initial registration.

[…] proposal is cross-posted at Falkvinge on Infopolicy and QuestionCopyright.org. Regular readers of C4SIF will find it, if anything, more preserving of […]

Responding to a few commenters at once here:

I should have mentioned in a footnote that we originally published this idea five years ago at QuestionCopyright.org. The explanation in that version wasn’t as clear, there was no graph, etc, so since the climate for reform seemed to be slowly improving, I decided to rewrite it and post it more broadly this time.

The only substantive change between the version from five years ago and this one is that the original proposal contained a significantly longer initial free registration period — a year, five years, something in that neighborhood. This was for the reason some commenters here have observed: it hews a bit more closely to the current system by giving the author a chance to do business under a full monopoly for a while before having to worry about the registration fee.

In the revised version, I reduced that period, feeling that avoiding an extended period of untempered monopoly was important, for example in the case of a book where an immediate translation would be desired by many (say, Yang Jisheng’s recent book on the Great Famine caused by Mao in China). If one wants to address the difference in scale between individuals and corporations, there are other ways to do it. One way is to have a sliding scale of percentages such that higher declared values incur not only a higher absolute fee but a fee that is a higher percentage of the declared value. In other words, as the presumed value shifts into the kind of territory where only corporate resources can be expected to profit from it, the registration percentages shift accordingly.

If the complaint is simply that in the new system, it’s harder for individuals to hit the jackpot, my answer is — especially with regards to patents — stop living in a myth :-). The idea of the lone inventor, struggling at her lab bench, Thomas Edison-like, until she comes up with the genius idea that brings her wealth beyond her wildest dreams is a fantasy. With very rare exceptions, that’s simply not how invention happens these days, and the corporate advantage in the current system is already very lopsided. This proposal improves that situation by at least opening up the possibility for interest groups to make common cause and liberate things that otherwise would have remained under monopoly.

Furthermore, to the extent that possessing a monopoly does make someone wealthy beyond their wildest dreams, that only happens because they exercised the monopoly powers (see, for example, J. K. Rowling and the suppression of almost all unauthorized Harry Potter derivatives, despite a vast and creative fan base). Do we want a system optimized primarily toward large corporations controlling vast amounts of cultural capital, and secondarily toward generating the occasional monopoly-based new millionaire, or do we want a system that at least gives freedom a fighting chance? We can’t have both.

Peter is quite right, by the way: the distinction between liberation and buy-out is crucial.

No long-term public interest is served by the forced transfer of the monopoly from one party to another. The point of the mandatory transaction is to remove the work from monopoly entirely.

If you want to purchase the monopoly from the current holder, you are free to do that (and thus be responsible for the valuations and registration fees thereafter), but that’s totally different from the liberation transaction. They shouldn’t be confused.

I’m not too keen on the idea of allowing people to revalue right away in response to an offer, because that sets up the same moving-target problem discussed early in the article. However, there might be subtleties to that dynamic that I am missing. And hmm, allowing a lowering of declared value — and hence perhaps refund of some of the fee? — at any time, including in response to an offer, might be interesting.

What would a scheme like that do to the GPL?

Also, what would it do to Open Source under BSD type licenses, where the only benefit the author asks for is being identified as the author of the work?

The major protection from copyright that the creators have for unpublished works, is that of bad publicity, as they probably cannot afford the costs of civil action to protect their copyright. If a publisher ignores their copyright then other will not offer the works to the publisher. Once a publisher has the right to a work, they can usually afford to defend it in the courts.

Where creators are using alternative Internet models of publication, the usually use a CC licence, and do not worry about free copies floating about the Internet. The main problem facing creators is obscurity and not piracy, as the latter get their work known to a wider audience.

In general people will pay the creators that they become fans of if they can. However at the same time, few people will buy a work from a creator that they do not know without sampling their work first. Copyrights only have a minor part in this relationship between fans and creators.

Copyright makes some sense when publishers are expending money up front to produce physical copies of works, books, records, CDS and DVDs etc., as a means of protection against a commercial competitor publishing the same works in competition with them. However the early history of American copyright shows that this is a weak role, as British authors were able to sell manuscripts to American publishers, when they did not need to respect British copyright. Also note that the 9/11 report sold well in its printed version despite a free electronic version being available. Also note no other publishers jumped in although the work was free of copyright restrictions.

Publishers want perpetual copyright not so that they can benefit directly from older works, but so that they can prevent them from competing with new works. This is a means of reducing the competition for attention against new works. However, when physical copies were required, control over production served the same purpose, is was just not economically viable to produce same quantities. With electronic copies, their is now cost of production, only a minute cost of storage and distribution. This does make some sense for extending copyright, as profit to the publishers can come from number of works sold, regardless of the quantities sold for each work.

The impact of copyright on society and culture however is significant. In part this is because the non commercial activities such as fan fiction, making remixes etc. have both become easier, but more importantly visible to the publishers because of the Internet. Creators often learnt their crafts by copying and making derivative of the works of others. Also using derivatives is how people made comments to each other and circulated ideas. Now instead of circulating such works by mail, they are circulated on the Internet.

Cultural works have also always been thing that could be loaned, and swapped, where loans could be between friends, or more formally from a library. This, along with radio and television were how people discovered the creators that they liked. The copyright maximalists are trying to prevent any such activity, especially where it involves electronic copies. This poses a significant dangers to society as discussed in my post on this article.

This reuse of works is what makes a culture, and efforts to stamp this use out is damaging to culture, as it deprives people of the means of learning how to use the artefacts of their culture. This includes the over zealous collection of fees by various performing rights societies, which make it expensive for pubs and other public spaces to permit impromptu performances.

The final point is is it reasonable to price culture and knowledge so that it is out of the reach of the poorest people. In effect should the perceived problems of piracy be used to prevent the poorest people from enjoying culture, and more importantly possibly gaining the knowledge they need to tackle some of their own problems.

On balance copyright, and patents for that matter, have become a problem and a major drain on society, and need to be abolished. They have become a means to controlling competition and enriching lawyers.

[…] second article, The Declared Value System: Managing Monopolies for the Public Good, was written by Karl Fogel over at Falkvinge & Co. on INFOPOLICY. Fogel proposes a fix for the […]

With any proposal like this, you have to think about all the ways the system can be legitimately gamed. My personal view is that simple regimes are harder to game than complex regimes, and the declared value system gets complex rapidly. (Its an interesting proposal, one worth thinking through.

From the creator side, a big problem with this system is that the market value of creative works is exceedingly difficult to predict. Big name artists are the exception, but even for them, variances are large.

The creator-side response would thus be to find ways to aggregate the risk. One way this could occur would be for creators to retain fee-paying companies which would collect large fees on the hits to cover fees on the non-hits. And perhaps pay creators compensation if they failed to cover the fee on a hit. The fee-payers would develop sophisticated mathematical models to insure that very few “hit” works would escape their fee collection systems. And of course the fees would be passed on to consumers.

Another creator-side response could be to aggregate their works. So 1000 creators would bundle their novels and take out a copyright on the entire bundle, and declare a value 1000x the value they would put on a single work. This would make it hard for the public to pick off individual, heap works.

I’m sure you could devise many other similar games. The governing law could try to anticipate them at the cost of increased complexity.

Much smaller changes, such as the ultra-simple measure of requiring a copyright holder to register every 5 years (no charge) with working contact information, could have a larger benefit/cost ratio.

Eric, thanks — your point about gamability is spot-on (I hadn’t even thought of the bundling idea), and simply just requiring a small fee and a re-registration every year or every 5 years would do a lot to solve the same problems.

I’m not sure whether simpler systems are less gamable than complex ones — that’s a deep question. But comprehensibility has other advantages anyway. It may be that the most valuable thing about the Declared Value proposal is that it’s one of many that draw attention to the “costless monopoly” problem, and not that it would be the best solution available to that problem. (Still, I’d rather live in that system than the current one!)

[…] The Declared Value System: Karl Fogel describes an alternative to current copyright law (CC0; link) […]

If you like great food then you will no doubt love Cheesecake Factory

recipes. The “petit” style can be used in several professional web sites among them the particular recipe internet sites which make the final blog

very attractive and competitive to other recipe weblogs.

Those who do this are headed for trouble, especially those

who try to do this for a business.